Whit’s workshop honestly wore him out. He would become visibly agitated, as he critiqued our stories, his face flushed, his voice raised. And he put so much effort into marking up our manuscripts that somehow, he never wrote much himself, even though a lucky break had let him pursue writing full time for a number of years. (A situation I’ve been in myself; the luck and the not writing.)

Inside us all lives a creator, an editor, and a critic. Engage that critic too fiercely, rev up its engines, and it will crush every nascent naive, sentimental, derivative impulse from the get-go. Watch that internal critic shut the creator down while the editor, and the rest of the world, shrugs.

Could Whit practice what he preached? Not easily. Themed anthologies with deadlines became his salvation. When he did finish and submit stories, they were good. Pretty damned good, when you factored in the fact that he wrote so few. He progressed faster, further, with a handful of stories, than anyone I’ve ever worked with before or since. He seemed to do it through sheer force of will.

He’d raised the stakes for himself with all that critique.

But you could tell, it was painful, caring so much, about how little we could make him care. And so Whit quit the workshop, to write on his own, publishing ten stories over a ten year span.

I inherited the Weasels. We were of course, at that point, the Witless Weasels, which was our nameless group’s not really name.

My wife and I had moved to Boston from Jamaica Plain, and then, to Cambridge. Ok, we lived on the Cambridge Somerville line across the street from a creepy bomb-shelter of a bar called The Abbey Lounge, but it was Cambridge, dammit. Our living room was huge, under a big skylight on the third floor of a small apartment building. We had two sofas facing each other and a few chairs that sat a dozen people easily. A big dining room table off to one side was perfect for stacking manuscripts.

At the workshop’s most productive stage the table would support five or six piles of short stories, each stack of ten stories somehow impressive. What my friend Anthony Butler once referred to as ‘evidence of industry.’ Every two weeks people would walk in with a stack of laser-printed courier 12 point double-spaced manuscript under one arm, walk out three hours later with a different stack–composed of everyone else’s stories.

The workshop, already important to me, became the focus of my life.

I had more writing time than most. I had split my full time McJob running an imagesetter at a graphic arts service bureau and ended up with four days a week in which to write. (and three 12 hour days to work.) I quit that job and became a half-assed freelancer, which was even more flexible.

I did write, every day, but I had a hard time finishing things. I’d drink a pot of coffee every morning, write five or six thousand words of email or USENET posts (the paleolithic version of Facebook) and finally crank out some fiction.

I’d start every story with high hopes, write a few thousand words, plot it out in my head, and eventually encounter myself on the page, my limitations, my ego, my hang-ups, my misery, my impatience, my insatiable desire for love and acceptance, my inappropriate lust, my weakness, my despair, my anger.

So I’d stop working on that story and start another.

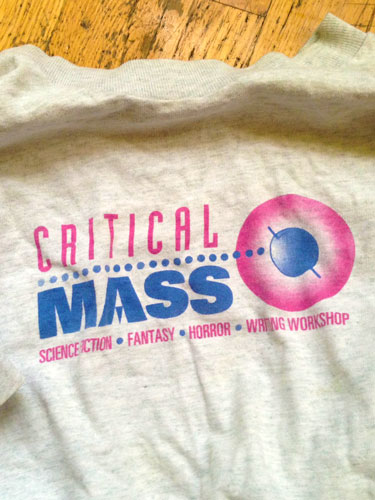

By now the workshop was stable at around 10 people, who were getting to know each other pretty well. I scouted MIT’s science fiction writing class taught by Joe Haldeman for members. I joined a group of local Extropians and Cyrionicists (you know, people who are going to freeze themselves after death.). I started going to local SF conventions and making friends. Somewhere along the way, I made an executive decision, and named the group Critical Mass. Most people liked the name. A few hated it. I decided I could be autocratic, this one time, so we’d have a goddamn name. I suppose this marks the beginning of the workshop’s decline.

The best known writers to come out of that room were Michael Burstein and Mary Soon Lee. Michael was the 1997 John W. Campbell award winner, an Analog author, whose anthology “I Remember the Future is well loved. Fifteen of the 17 stories were nominated for a hugo or nebula award. Mary Soon Lee published seventy two stories over a period of a decade, breaking into Analog, Interzone, and F&SF, and getting a story into David Hartwell’s Best of the Year Anthology. There were other accomplishments, other points of light as well; one of my MIT finds sold a story called The Portable Girlfriend under the name Doug Teirny, which made it into the Years Best Erotica in 1997. Drax got a piece in Gordon Lish’s The Quarterly. Being discovered by the guy who discovered Raymond Carver? Pretty cool.

Those who stuck with the workshop got somewhere. Always. Maybe only a few sales. But something, everyone got something. Steven Patten, Rick Silva, Dawn Albright, Sandra Hutchinson, Michael McComas, Jenise Aminoff, Sandra Hutchinson, Gil Pilli, Mark Sherwood, Simon Drax. Many of us became close if not exactly friends, united in this effort; colleagues… comrades.

Here is the thing; love and friendship among writers is sometimes conditional on the writing; leave the church of writing, and you’ll leave some friends behind, too. It’s not that you’re shunned, either. The drifting apart is mutual.

But the person who took the workshop to the next level for me, personally, was Mary Soon Lee, and her process.

1. Finish almost everything you start.

2. Workshop everything you finish.

3. Listen to critique, fix any typos or glaring errors that emerge, but don’t rewrite anything unless you feel like it; and you probably won’t. Just send it out to your top magazine choices. If you think it hasn’t a hope in hell of selling to your top markets, send first to smaller presses that like you.

4. Keep it out until it sells or you run out of markets.

This worked for her pretty well.

I started finishing things. Every two weeks, a new story, on the table. They started getting better. I’d sold that first story to Aboriginal SF; after that I sold another ten stories or so; if two more reached publication without the magazines that bought them folding, I would become a SFWA (Science Fiction Writers of America) Professional science fiction writer.

Um. Professional here doesn’t mean you make a living; it means you sold three or more short stories (or one novel) to someone who distributed them as books or magazines by the tens of thousands.

The thing is, my internal critics barely let me write at all. Copying Mary Soon Lee forced me to finish all those stories of mine I hated, which I eventually would grow to love as I finished them, and hate again as they were rejected. Then, like Whit, I upped the ante, raised the stakes, and decided to apply to Clarion.

You know. So I could strengthen that internal critical voice.

You see where this is going.

Stay tuned for part 4: Post Clarion Wipeout: Nineteen Years in the Dark