Let’s return to a time before I had children, before I went to Clarion, before the internet bubble, before my so-called professional identity, before we had a mortgage and a car. I was a guy who’d scraped by for over a decade, in high-school, and college, and after a series of, oh, let’s call them medical problems, finally graduated from Syracuse University with a B average and a BFA.

Only took me the seven years.

Anyway, my first writing group dissolved, a few meetings, a few pieces, important, but transitory. My friendship with Ron and Marty Hale Evans continues to this day, but Steven Burke, his novel about the doomed Red Sox and the Crows, and the Vogon Poet, are long gone.

I do not remember how I found Whit Pond’s nameless group. Was it a flyer in a bookstore? Maybe the Science Fiction bookstore Pandemonium in Harvard Square? I took the Orange line to downtown crossing, caugth the red line and traveled through Cambridge into Somerville, Porter Square. I emerged from the insanely deep subway stop, up the three sets of escaltors, following directions from the flyer carefully, ending up at new-england ranch house. The houses in Somerville reminded me vaguely of the those in suburban central New York, but the lots they inhabited seemed shrunken, the yards tiny patches of weeds or concrete blocks, the houses packed in side by side in a frightful density. Insufficient tree cover made the neighborhood look a little washed out, dingy.

Still, it was nicer than were I lived, in a brownstone apartment building in Jamaica plain.

The man who opened the door for me was middle aged, thick in the middle, with longish receding graying hair. He had a mild southern accent and radiated a calm and determined intelligence. He shook my hand, smiled somewhat sadly, and welcomed me to the group.

Whit’s critique group style was anarchy. We didn’t take turns. We interrupted each other. We shared a few stories every two weeks, and we talked about what was wrong with them. We didn’t talk about what was right with them, for a few reasons. One, there wasn’t much good about them. Two, Whit was a brutally honest critic, and he set the tone for the group.

Whit told us, over again, he didn’t care. We weren’t making him care.

“I don’t like your characters. I don’t know what they’re doing. I don’t care about them. I don’t care about what’s happening. By page ten, I hate everyone. I’m hoping they all die horribly,” was what he told us, mostly, and mostly, it was true.

Whit’s critiques were breathtaking. The word flensing comes to mind. They made my heart hammer and my palms sweat. They hurt. And you knew, though, that Whit was only being honest. He liked science fiction, he liked stories. He just didn’t like yours. And, after Whit had pointed out their failings, neither did you.

And so I started to think, seriously, and continuously, about why we care about the stories we read. The made up people in the them. The bullshit situations. The make believe worlds. And suddenly, science fiction, a literature of ideas, became to me something else entirely; writing was really about character and emotion. Why do we care? Why do we care?

Every word I write now passes through that filter. Why should anyone care?

Workshoppers came and went; not many people could stand more than a few Whit crits, a few whittings. But one day, a pretty young woman showed up, in the pouring rain, seven months pregnant, looking like she was going to pass out. We brought her in, and listened to her. Let’s call her Rain. She’d sold a story to a goddamn magazine, to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Fantasy magazine, a story called Black Ribbon.

She brought a copy to a meeting, and I read it. A lovely short story about a cursed, imprisoned girl, bewitched into something toxic. Finally she is sent out by the people imprisoning her, to go to a dance, a ball. Where she dances with a host of royals, all of whom will be killed by her embrace. She’s just happy to be out of the house, dancing. Creepy. Weirdly moving.

I cared. It was good. And this woman had written it.

She taught us about the rules of workshopping, which she’d done before with actual writers who actually published things. She was like some ancient goddess bringing fire to a bunch of grunting cave men. We would take turns. We would not interrupt each other. We would use a timer. The author would speak at the end. We would go around the circle. And then, with her in place, the group began to solidify; people started coming back, week after week.

Rain’s life, as it turned out, was a shambles. She’d been impregnated and abandoned by her worthless hippy husband, who had taken all her friends with him when he left her. She’d clawed her way from the bottom of a pit of murderous depression to come to the workshop that night, struggling with pregnancy releated blood pressure issues, staggering through the damn rain to bring the grunting cavemen fire. She came and she kept coming. She brought her baby with her a few times, because she didn’t have a lot of resources, being far from her family in Ohio. She dated one of the guys in the group for awhile, a strange angry bearded man named Jeff.

I talked her up to my friend Peter. They were married the day after I came back from Clarion.

First and foremost, though, Rain was a writer, who had sold a story to a magazine, and she knew how a workshop should be run. Whit, it must be said, took her advice, and while it didn’t soften his critique, somehow,he became more bearable, because his became just one of a set of opinions given roughly equal weight. He still set the tone, but the group was now bigger than just him. The people who stuck were the people who could keep bringing stuff in. Some would become my friends for life. (but so many would fall away. Rain and Peter included. Life is like that sometimes.)

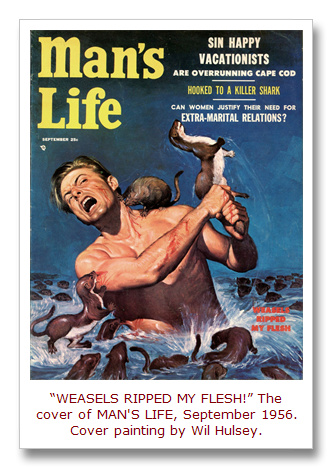

The group had no name, but we joked, sometimes, about being weasles, ripping each other’s flesh. Like the Frank Zappa Album cover above.

And the day came after a year or two when I would write a story that Whit didn’t hate.

He looked confused, at that meeting, flipping back and forth in the manuscript, trying to say, what it was he usually said, but he couldn’t. Because I’d made him care. He would call me, later in the week, at home, with a new series of complaints about the story, why it was deeply flawed, but it was too late. I’d sent it out.

The story was called Dollhouse, and it was my first professional sale, sold to Charlie Ryan at Aboriginal Science Fiction. In 1994.

Like Rain, I’d sold a story. I had my sign! I knew what was I doing.

Or so I thought at the time. For a while.

Until Clarion.

If you found this essay inspirational, interesting, amusing, whatever, join my mailing list. I mean, if you want to. I can’t make you. But I’m asking. Because you read this, and that means I sorta love you. Um. Okay, this got awkward. Boundaries! This is the link to my mail chimp page.