So I found this site Young People Read Old SF, by accident, blundering around the web; it was inspired by a quote from my friend Adam-Troy Castro:

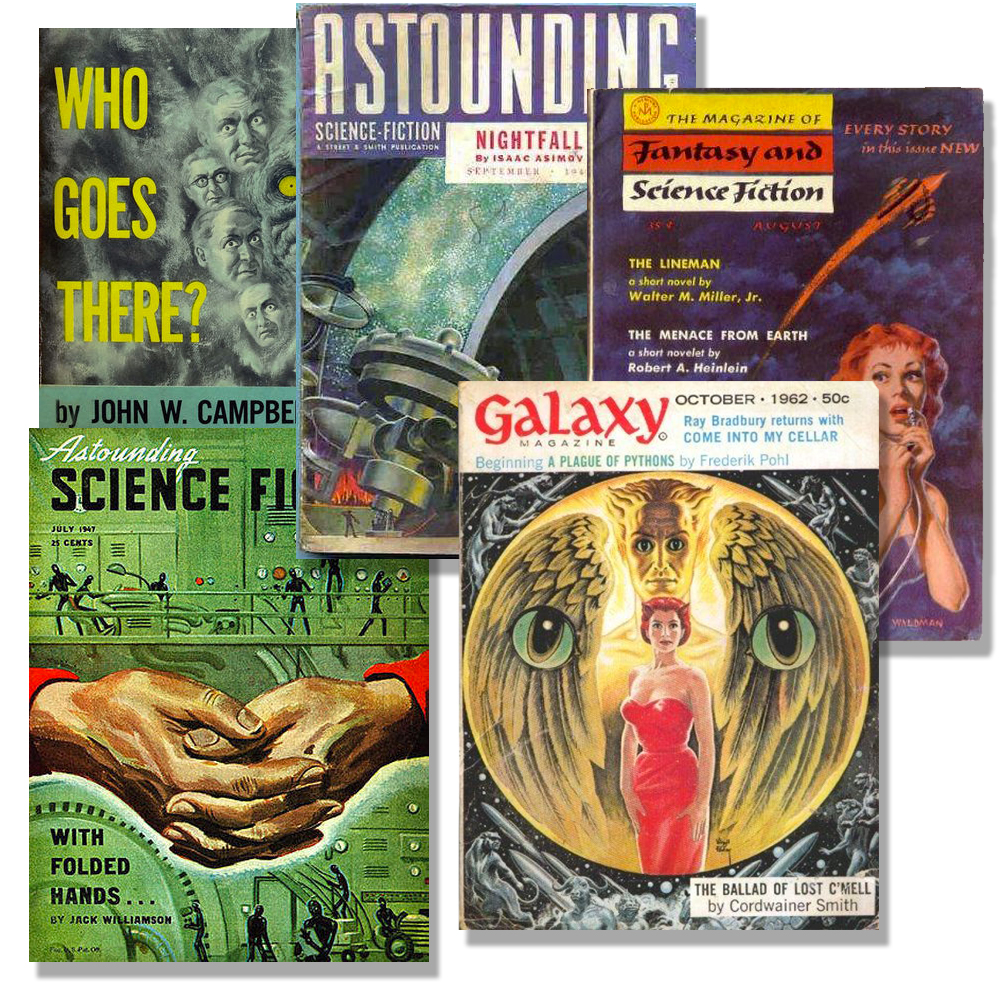

…nobody discovers a lifelong love of science fiction through Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein anymore, and directing newbies toward the work of those masters is a destructive thing, because the spark won’t happen. You might as well advise them to seek out Cordwainer Smith or Alan E. Nourse—fine tertiary avenues of investigation, even now, but not anything that’s going to set anybody’s heart afire, not from the standing start. Won’t happen.

Someone took him up on this, and created a site and drafted some young readers; you can tell the old fan who set this up pulled a crop of stories that he felt had serious merit, and in fact, many of these stories are ‘classics’ from the SFWA Hall of Fame collections; older stories voted on by the Science Fiction Writers of America in the 70s as being award worthy, from before the time the Science Fiction Writers of America existed.

You can tell that the older fan who put the time and effort into this expected these stories to be better received. Looking over the list, I expected the stories to find at least a few modern fans.

So, TL;DR, Young People Really Hate Old SF.

One reader delights in hating everything, which I expected; another reader, after giving up on the idea of representation, of having POC and female and non heterosexual characters, more or less hates everything regretfully.

There are a scattering of positive comments. But mostly, boredom and hate.

Part of me resists this analysis, strenuously. What about the GOOD things in these old stories? How can you hate someone in the 40s for not getting details right about the 2000s? Isn’t it amazing the stuff they get half-right? Aren’t the awkward stabs at portraying some racial and gender progress sort of… charming?

No, modern readers tell us, they are not.

But part of me sighs and relaxes. I’ve said for a decade now that SF doesn’t age well. A handful, and I mean, literally, a handful, of titles will survive each decade in any meaningful way.

Part of me exhales and counts to ten and closes its eyes and says this is Okay. We write for ourselves, for our readers, for our editors, for our time, never knowing to what degree we are embedded in a fleeting moment, or to what degree we speak to the ages.

Not our job to know that.

In a broader sense, I feel a greater sense of freedom, with regards to mining that old content, those 1000 books I read from age 13 to age 18, for tropes and moments and emotional highs and translating that into something that can still be read and enjoyed today.

Either finding the universal and scraping away the period ‘isms’ (sexism, racism, nationalism) or by infusing the content with modern values of inclusion and compassion and diversity.

Maybe I’m just making more dated ephemera. Maybe I can find a book that lasts in me. Either way, there’s work to do. Much more work than when I thought of those ‘classics’ as being things I could still point a young reader at.

To any young reader who enjoys any of the 1000 books I read as a teen, I say, awesome, welcome to the club; to the readers for whom this stuff is intolerable, who read the new stuff I’m reading and writing now, I say, awesome, welcome to the club!

We’re a big tent. People of the future. Denizens of faery.

Our work goes on for as long as the unknown beckons.

We’ve been discussing the comments made by the readers there—less than half a dozen people—on a group I’m in. The consensus is that they’re morons, judging yesterday’s works by today’s standards.

Hey, let’s object to the film “Casablanca” because it’s in b&w, and the women aren’t the most important characters!

Morons…

I wrestle with a lot of this stuff. I believe cosmicism can be saved from the racism of HPL, for example, but can’t argue with writers that HPL thought of as subhuman not wanting his head leering at them from their bookshelf. The thing is, we have one machine for valuing and forcing people to read old stuff; academdia and lit crit; our classics are outside that system, which itself struggles for relevance. These are my classics, they’re in me, they never leave, but I am going to feel free to reinterpret these things, explore them anew in a modern voice, in a modern light.