So the reviews are creeping in for my story Grandmaster in the current March / April issue of Analog, and they fall into two camps.

- Pretty good story, moving, not sure who this character is supposed to be.

- I found the story effective, but had to ask this old fan who this woman was, and now I’ll tell you.

Backstory. I’m fifty three, which makes me of a generation that read all science fiction. All of it. We read backwards and forwards, because the genre wasn’t that big, and we couldn’t get enough. We weren’t these super powered geek nerd reading machines, (well, we were but…) it’s just that before Star Wars, the world of SF was pretty small.

We couldn’t get enough.

Star Trek was moderately big, at seventy two episodes, three years, it had spawned it’s halo of novelizations, but before next generation there was over a decade of puttering about with a project at Paramount that never turned into a show. (Phase Two, it was called; bits and pieces of it end up in the Star Trek Movie and the TNG, Next generation.) But let’s face it, Star Trek is pretty cerebral. Most people… aren’t. The unbelievable appeal of genre materials wouldn’t be readily apparent until George Lucas was forbidden from remaking Flash Gordon, and so he ended up with something much, much better. Star Wars. Space fantasy, capturing the energy and spirit of the SF pulps of the 20s, 30s and 40s… in the late seventies…

Star Wars was always a kind of Happy Days of movie SF; it was always retro.

Picture Fonzie saying, “Aaaaaayyyyyyyy,” here if you want.

I remember reading after Star Wars, the ceiling was raised, and the bottom fell out. You could make a lot of money with an SF property, so there were many more of them, and you could lose your shirt. Of course, what drove us fans nuts was that so few projects were in any way connected to SF writing or the classics of the genre.

We were bludgeoned by pre-asimovian robots running amuck and giant insects we knew could never actually survive because of the square cube law and Martin Gardner’s wonderful essay ‘on the importance of being the right size.’

Anyway, fans of a certain age ended up reading at the very least representative hunks of stuff from the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s, as well as books being written in the now of the sixties and seventies. There wasn’t a huge split, into media related properties, movie tie ins and franchises, and Everything Else. There was just the everything else.

SF author culture of the 40s, 50s, sixties was supposedly oddly welcoming and supportive of new authors. The reasoning went, that most people made modest livings, writing SF, and that real fans bought or read it all, so it wasn’t a zero sum game; SF authors weren’t really competing for fans in a Darwinian show down. There was a cattiness and nastyness in Literature and Bestsellerdom, that SF lacked. Or so they said.

I came of age in the 80s, as the culture was wracked by Reagan and Just Say No, Morning in America, the end of the sexual revolution, the beginning of the great divide, the waves or privatization and income inequality that would radiate into cyberpunk and then become so ubiquitous that it wasn’t popular as fiction.

So, for me, that pre-sixties era was a golden dream, a dream of my father’s generation, or half a generation younger; this time of great SF camaraderie; of John W. Campbell at Astounding writing letters or critique back to Heinlein, Clarke, and Asimov longer than the stories they’d submitted themselves.

At some point I bumped into the stories of The Futurians, a group of SF writers and editors who emerged from the fractious world of SF club culture to become a powerful force in SF publishing and writing. Yes. There was a SF club culture. Don’t laugh. Hey, think about the monstrous size of something like Comicon. Now stop laughing. That starts here.

While mostly men, there were women in these groups, and these women wrote and edited and dreamed and argued and smoked and slept with and married and divorced and remarried these men. Women were a vital part of it. Mary Shelly birthed the genre with her book Frankestein, and women were always there, always a driving force…

But C.L. Moore used the initials so that her gender wasn’t evident on a byline.

My Dad told me that Moore and her husband, Henry Kutner, whose life would be tragically cut short in the 40s by an abrupt heart attack, tag team wrote under pen names. It was anybodies guess really, who wrote what of the books they wrote together. To a lonely teenager, the idea of a writer wife you wrote with was the most romantic, attractive, and erotic thing imaginable. It haunted me for decades, even as I stopped being lonely.

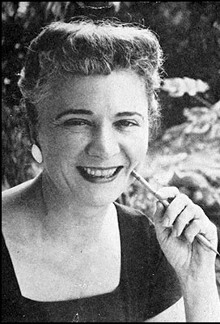

While looking for more C.L. Moore to read a , beyond a few heavily anthologized classics, I spoke to Michael Morano, a Boston area horror novelist and reviewer, and he told me the story of her uncollected Grandmaster award.

“Her second husband’s family is ashamed of SF. It’s hard to find, her work is out of print but not public domain. Her husband said she was too far gone with Alzheimers to accept the award. So they didn’t give it to her,” Michael said to me.

And something in my heart broke.

So, big reveal, I’m a progressive and a feminist and supporter of GLBTQ rights, with GLBTQ family, but I’m also a pretty regular white-het-cis middle-aged guy, and my resonance with and emotional response to feminist and racial struggles varies. Intellectually, I’m always there, but emotionally, I know, some stories hit me in the gut, and some don’t.

But Catherine Moore I had read, and loved. Kuttner I had read, and loved. I had loved thinking of them writing together. I’d not known about the Grandmaster award. And suddenly the ghost of every unsung woman hero , every forgotten female pioneer, tapped me on the shoulder and when I turned, blinking, she punched me square in the face.

A character from a failed novel leapt in the time machine she was building to give C.L. Moore her award, an asperger-ish nerd girl from the year 2056, who I also love, even if her novel failed. But things with Autumn, that character, never run smoothly. She makes interesting mistakes. Which doesn’t mean that I don’t love her, and Moore, and feminism. But what began as a kind of progressive polemic ran headlong into the tricky business of character and unintended consequences and… well.

Read the story. It’s very short. Hopefully it does something for you.

It makes me cry, every time I read it.

It made me tear up even though I didn’t recognize who it was. Thank you.

You’re more than welcome. There’s even more to it, but I don’t want to talk it to death. It’s not that long a story. But I generally enjoy the stories behind stories myself. And that image, of the tag team writing, on typewriters, still gives me shivers.

I just wish you would have included some Googlable name for us young readers. I spent a lot of time trying to find the right way to search for the pseudonym “Anderson MacDougal” and get something other than irrelevant news stories before I switched to looking for somebody talking about the story itself.

And I certainly couldn’t read this story about an obviously real person receiving an honor deserved but not given and then walk away content to not know who we’re taking about. That would be disrespectful to Moore and to you. That would just be wrong.

First of all, I am delighted beyond belief that you read the story, know who Moore is, and care. And you’re younger than fifty. How did you find it? Are you an Analog reader? I fictionalized the story for a bunch of reasons. I had intended for it to be this pure tribute to the grandmaster, but while writing it the characters of the two women, the modern woman and the woman from the 40s and 50s interacted in unexpected ways.

The story is a romance, because everything I write is romance, no matter who the POV is, and in getting her award she learns that her husband will die or they will split up, and we’re left wondering if the award was worth it.

I had not wanted the story to have this dark note, but it hit me hard; Moore’s intelligence and insight loomed up as I was writing what I’d hoped would be this pure tribute and the water got muddy, but I couldn’t deny the feelings bubbling up on the page.

We have this belief about artists, sacrificing human relationships for art, the art the highest calling, and how artists are sometimes or often kinda shitty people. I wanted my story to grant her that kind of creative dedication and at the same time, the reality of the great sacrifices women have traditionally been called upon to make for children and family reared up and I was grappling with a modern view of gender and a more traditional view and wondering which was the truth of that moment.

This is something I can never really know. No amount of research could discover that. So I built the names out of the fake names used by other writers in that era (including Heinlein, who wrote under similar pen names)

So I made my Moore the superior artist of the two; the one who could see the darkest ending, to their great novella Vintage Season, the ending that was also the truest. She must go forward knowing that personal disaster of some sort awaits.

Their shared work is also an act of love… but her love is less selfish than his. Not because of gender essentialism. Just because. Her story is a gift to their relationship AND an expression of her genius. It’s both at once. So she is a great artist AND a woman of her time. There is no contradiction. But to us, this is impossible to fully embrace in our time. If feels regressive.

This is what I think the story is about now. But I don’t really know. This is all after the fact rumination.

The story bothered me and still does. It may be more about my own deeply ingrained romantic ideas than anything about Moore.

I also love the story dearly and am glad to have written it. I hope you got something out of it.