My best friend (I had four) when I was a kid went to Boston to go to college. I knew our friendship would fade away, because that’s what happens, but miraculously Mike, one of many Mikes (and Daves and Steves) of the era, moved back home, and we ended up at Syracuse University together.

He rented a basement apartment with a soon-to-be full time Deadhead, and finished his engineering degree, while I lost my mind for a year and floundered about scraping together a BFA.

He had an elective, one of few allowed him, that he took his senior year, shortly before I went mad called The Doors of Perception, which was an English course about transcendental experiences which included the Alduous Huxley text of that name, and often, a party at the end with the teacher where everyone dropped acid.

The 80s hadn’t totally kicked in yet, there were fumes of the sixties and seventies still wheezing through the culture. Me and my friends got high on the fumes as we avoided punk rock.

We met at the Teacher’s apartment. His name is so close to the surface of my mind, but I can’t retrieve it, and Mike would come and go once more in my life, to be gone again, living a few miles away, but in another world.

I remember how cool the teacher’s apartment was, large, airy, filled with mismatched furniture covered in blankets and coverlets. They’d been pulled off the street. Coffeeshops in Seattle would adopt this look a decade later, this eclectic mix of comfortable used, upholstered, furniture, instead of hard seats and wooden benches.

The walls his enviably large apartment were stucco with dark wood trim, baseboards and rafters. We drank beer and ate chips and took acid. I didn’t take all that much acid, so I wish I could tell you I remembered the kind–microdot or blotter. Microdot was sacharine pills soaked in food coloring and a variable strength solution of LSD or something like it. Or soaked with nothing, as in the first time I took a hit of orange microdot, and nothing happened after the placebo giggles died away while Mike and I played pool.

I’m gonna say microdot. The teacher, whose name whispers in my ear every time I picture him, is in his late twenties or early thirties, brown bearded, cool, so cool, and smart. A teacher like my father at the same university, but very different. My father was a professor in a suit and tie. This guy was what we still might call a hippy.

Once we’d started to feel the acid he put on some music.

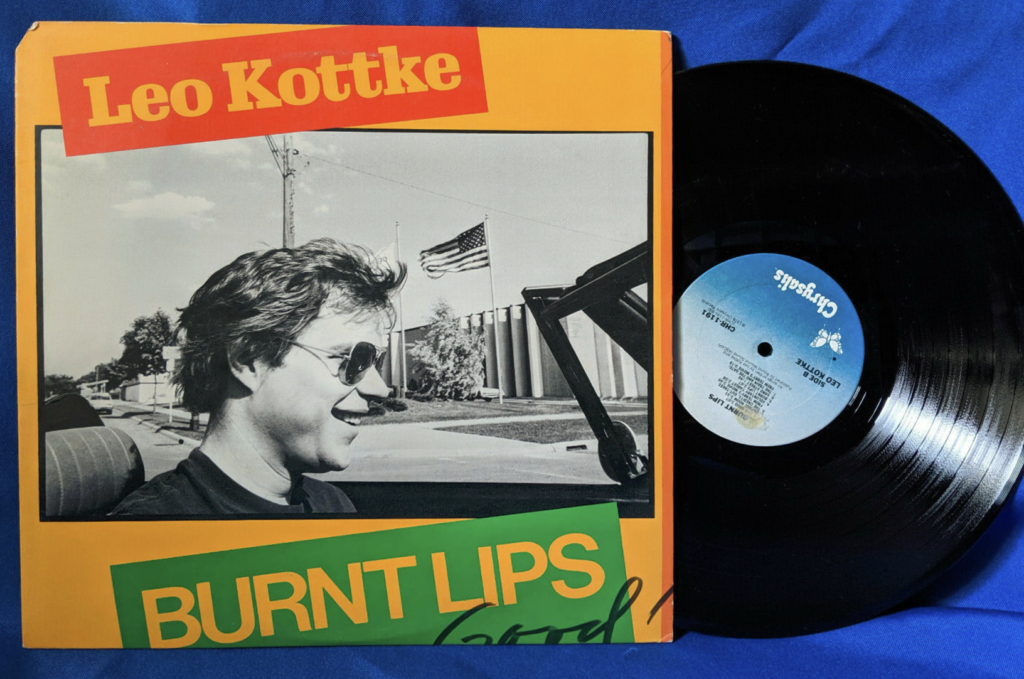

Vinyl, on a turntable, Leo Kottke’s Burnt Lips, and hovered over the spinning disk to drop the needle at “Cool Water,” which I would remember, the undulating slide guitar, the throaty vocal, until I moved to Jamaica Plain and bought the CD to play for myself.

We wanted to go for a walk in a park, so we drove to one I don’t think I’d ever been to before. At any rate, I didn’t recognize it. We talked and we sat on the swings and one by one we ended up staring into the starry autumn sky.

“Do you see it?”

“Yeah. Wait. What do you see?”

Because a flowing luminance shimmered before the stars, like the amorphous web of light undulating on beach sand under restless water.

“Wonder what that is,” somebody says.

“Maybe they pushed the button.” I say. We thought about this in the back of our mind all the time, back then. Reagan was a nightmare.

“Seems sort of laid back, for the end of the world.”

We imagined ions whisking through the upper atmosphere, glowing, radiating. If this was the end, we decided to be good sports about it, and to continue enjoying our evening. Which we did. Immensely.

Driving home, barreling down a street made strange by the cascading feedback loops in my brain, we hit something. Thunk. Something substantial. We kept moving. We never slowed down.

“Cat,” Tom said. His name was Tom. I have it now. “Nothing I could do.”

We were all sad, for a shamefully short time. But Tom assured us that there was absolutely nothing he or anyone could have done, even though the obvious, driving slower, was staring us all in the face. The cat had committed suicide. Our world wasn’t ending but the cat’s did. I still worry about that cat, twenty five years later. We should have stopped. But I was in the back seat. Along for the ride. I successfully refused to imagine the family that had cared about him.

We got back to Tom’s place and his roommate, a skinny bed-headed man with a bad cold, was there watching television.

“It’s so comforting,” he said. “When you’re feeling ill.”

We watched an incomprehensible black and white film together.

“They are all wearing these terrible hats,” the roommate said. I thought he was gay, in that way some men seem gay, in voice and manner, and this didn’t bother me. I’d been bullied for being gay, without actually being gay, so there was a kind of camaraderie I felt with the genuinely gay, even if I was still mostly clueless.

The scene cut to a group of men running in a hallway. Again, all wearing hats. Human life began to feel absurd.

The roommate blew his nose. His eyes were red. “More hats!” he said.

We were all intent on the movie. The sun rose relentlessly outside the windows, the light clean and fresh.

On the tube television a sepia-toned man with a swollen cowboy hat the size of beehive was talking earnestly with another man, also of course, in a hat, and we all thought this was the funniest thing ever.

The way you do, in that situation.

And the sun came up, and the night ended, and I went back to my first apartment on Dell Street, before I went mad, and Mike went back to his basement with the deadhead, and that evening would shine in my memory for years to come. We never hung out with the cool professor and the other English TAs again, and I’d stop taking acid after I went mad, and of course, because I would graduate and leave my hometown a year before everyone else did. I had a bachelors and they were getting masters, and the gang was gonna split up, and I would miss them. I followed my girlfriend to Boston, because I loved her and Boston had a future and everyone knew that Syracuse didn’t. And I told myself I wouldn’t miss it, even as I knew, I’d miss my friends.

And my life, that life, with those friends, ended and the cat’s life ended but the shimmering fallout, we thought we had hallucinated turned out to be a rare instance of the aurora borealis extending into central New York. Barely perceptible, they said, to the naked eye, but not to the eye opened by microdot. Blue? Red? Orange?

Cosmic light streaming through the doors of perception.

And not the world ending at all.

It’s 2021, and I ask Alexa to play Leo Kottke, and she plays him for a time, good songs I don’t remember, and finally, I ask her to play the song, Cool Water. Drop the needle on the track. I can’t wait for it pop up by itself.

And the song is beautiful.

Mike, this one is for you. If you ever read this, which seems unlikely, remember I loved you. You saved me when I was sixteen. I miss you, but it’s okay we don’t talk anymore. That happens a lot.

I wish you well.