My feed withdrawal and existential horror at the post-trump / mid-COVID / Climate-change-world-on-fire has propelled me back into charming futures we foresaw in the past. Charming in retrospect. We worried about nuclear war, in a delightful binary way, (World toggles from to STATUS QUO to CINDER) and we dreamed of galactic empire, or more modest things, like Niven’s Known Space.

Known Space, for the generation that consumed it, felt startlingly real. At least for the readership of mostly white middle class boys like myself who lived there. I could ask Steven Barnes, Niven’s later collaborator and POC, how it felt to him… I should…

Niven’s future displayed no significant racism. But there was a cost to this for the white reader. We were asked to empathize with some viewpoint characters who were described as non-white, mixed race; I could dig up the description but Niven took the earth’s population at the time of the invention of teleportation, I think, and shoved them in a blender, to arrive at a POC mix of Caucasian, Asian, African, Middle-eastern, and so on.

I remember the shock at that. I’d gone to school in a minority majority system until forth grade and my best friend was Chinese American, and still, still, it was amazing, to be asked to be a POC in a SF story.

The character Louis Wu, was kinda-sorta asian, I mean, the name, and I was being asked to live inside his head. I was an SF reader, though, so after that first moment of confusion, I thought “why not?” And as Wu was living in a post racial world, written by a rich white guy, he was a comfortable fit. After I bit, I felt very good with being Louis Wu.

Yay?

After the stunning racism of stuff like the Lensmen stories, and Lovecraft, people like Niven felt appropriately utopian, for a white professional class that liked to think that the womens’ movement and the civil rights movement, had bent the arc of history permanently, and had us coasting to eventual equality on autopilot. Without us white people doing anything else.

Niven’s ‘ism’ was planet-tism, or species-isms. Folks who never went into space were parochial; different planets might have different mind-sets based on different environments; space travelers were cosmopolitan, and aliens could be a little bit but not too weird and largely defined by species-level stereotypes. The character of Nissus the ‘mad’ puppeteer, is an example of Niven seeing species-driven character traits as existing on a spectrum. His people were risk-averse (cowards) and Nissus was ‘mad’ in his ability to interact with other species. To be in their dangerous presence. Puppeteer’s furniture was all melted looking, lacking sharp edges or corners, in case they tripped and fell against a dangerous surface. And Puppeteers were tripods!

The other thing I remember from known space was that religion had zero impact on any of the actions of the characters; everyone was some sort of rationalist. This works best for people who came from Christian stock, who have lost interest in Christianity, of course; as a Jew, or any faith in opposition to Christianity, one worries if your people of faith have all been killed off and or assimilated.

…and of course, there was no visible oppression of GLBTQ, because, well, there didn’t seem to be any. Again, this works if you aren’t GLBTQ.

The world without obvious oppression, written by folks who never experienced oppression, wasn’t new of course, but Niven at least gave us a few reasons as to why the old school oppressions were obsolete.

I just remembered the teleportation thing as the excuse for the uniform racial makeup. Making the future so fundamentally different means that geographical isolation might not keep us as separate. Though of course, folks stuck in coal-mining towns often won’t drive to the nearest city to start new lives; they go down into the mines and get black lung and die in tunnel collapses.

So… not sure the teleportation booths are gonna completely get everybody off of the farm…

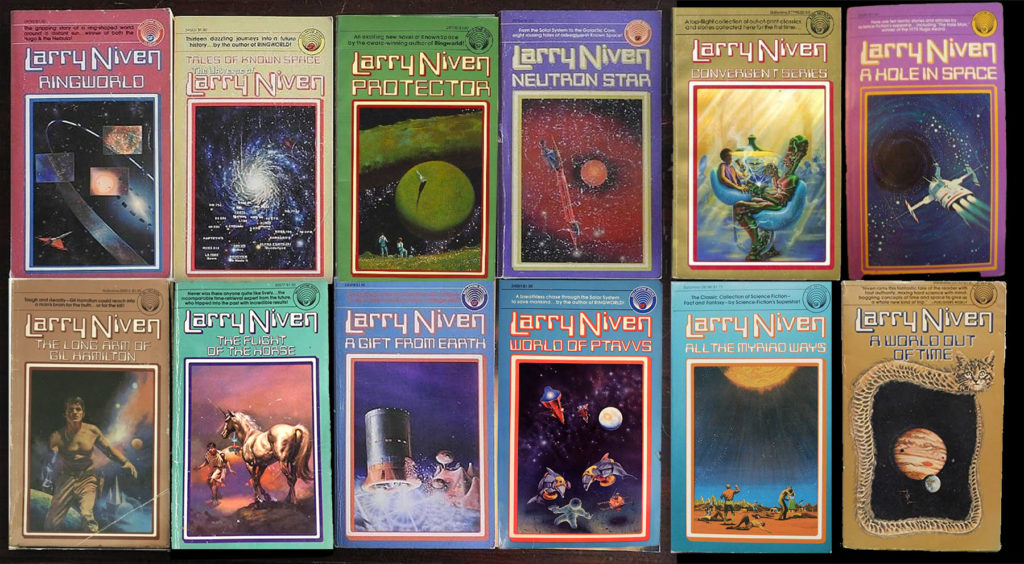

Anyway. Here is to Known Space; looking at the timeline of publications I realize that it’s written earlier than I thought, in the sixties. Ringworld is sort of the capstone to Known space, in a lot of ways, and its 1970 publication date means that, like the Beatles, Known Space was really an expression of the 60s. A mildly conservative expression of the 60s, avoiding a lot of the SF new wave. Really, if you think of it, Known space is a straight-line evolution of Heinlein’s Future History systematized in the 50s.

Which of course, I was devouring at the same time.

Hm. The timelines in the omnibus collections are similar, too….

At the time, so much of my privilege was invisible to me, in ways very common then, and still common now. But these texts dovetailed with that ignorance. Creating… indescribable feelings, at least, indescribable now.

I thought I was reading the future.

It wasn’t of course the future, but a future made for me, by someone a lot like me… but by someone without an ax to grind, or much less of one, when it came to gender and race. Even I could smell something rank coming off of a lot of old school space opera. Something a bit off in late Heinlein’s sexual wish-fulfillment fantasies.

Known Space, though, was a future I loved without reservations.

This was the place I wanted to go.

This is where I wanted to live.

Imagine that. The future as a place you would want to live in!