My father played pool with two contractors named Joe, and Carlio. One was my father’s friend, or so he thought, and the other one, less so. So they built us a split level ranch in the suburbs of Syracuse New York in 1973 one summer, creating a clean break with our old elementary school, as we moved in before the new year began.

My father played pool with two contractors named Joe, and Carlio. One was my father’s friend, or so he thought, and the other one, less so. So they built us a split level ranch in the suburbs of Syracuse New York in 1973 one summer, creating a clean break with our old elementary school, as we moved in before the new year began.

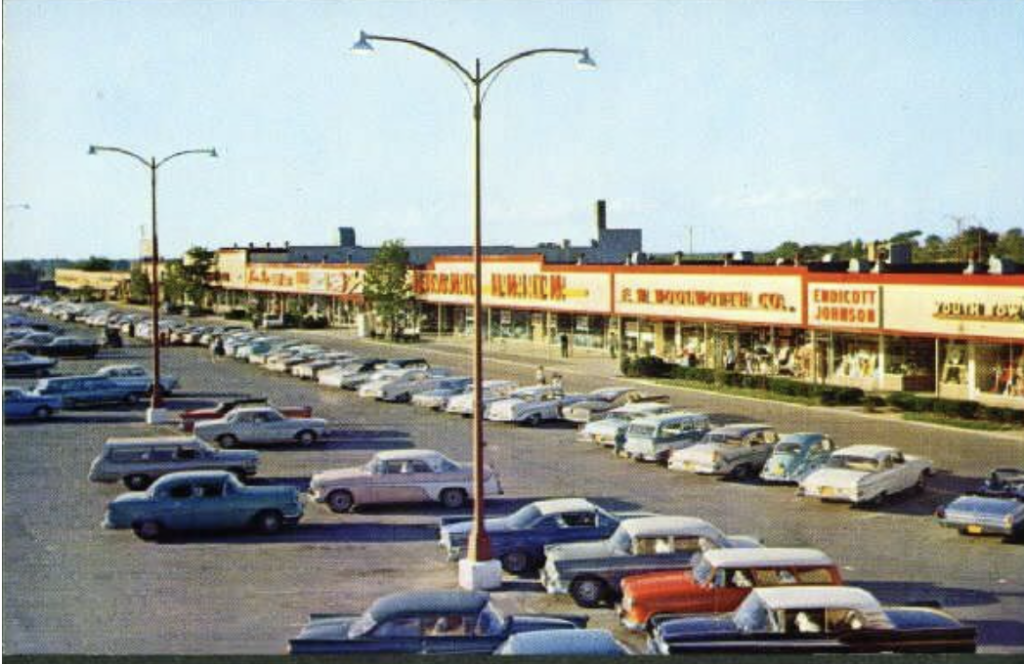

We moved less than two miles, from the city, to the suburbs, part of a vast white migration away from city centers into unsustainable suburbs. Nobody had run the numbers, or if they had, nobody cared, about the fact that as the infrastructure aged, in many suburbs, the taxes didn’t support fixing anything; the spread out houses, with the big lawns, with all that breathing room, were connected to grids that were stretched to the breaking point. Maintaining all the electrical and sewage stuff, fixing and plowing all those roads, for that population density, was kinda…

Stupid.

Oh, but the space a middle class person could afford. The distance from the neighbors. The two car garages, and the unfinished basements that could and often would be finished, the back yards into which decks could expand, into which swimming pools could be sunk.

No sidewalks for the kids to walk on, but who cared? Who needs parks with the swing set and sandbox in the back yard.

It seemed the most natural thing in the world.

My parents were academics, at that time one Ph.D, and one in the making. My mother from the deep south, with an accent that waned in the Northeast, and waxed on visits home, but was always there. My brother and I attended a city school, maybe 50% minority, which is and was something that is hard to sustain. The white people get scared and move out.

The school was I think, mediocre, in the way such things are typically measured. I scored very high on the Iowa exam, learned to read and do arithmetic by 4th grade, learned a bit of what we called social studies. I spent a lot of time in the library, looking at picture books of space travel by Willy Ley, whose paintings now looked kinda stupid as Apollo unfolded in the real world.

I was involved in a fight, in some way—we called it getting beat up, because me and my friends didn’t fight very well. Many of our classmates were much bigger than we were. My mother came in for a meeting with the VP in charge of discipline, (all schools have them. This way the principle can seem nicer.) and when she asked what was going to be done about the attack, the VP wanted to know what I had done to provoke it. What words I may have used.

She heard my mother’s southern accent loud and clear.

My parents decided to move that night.

About that word– my parents never used it, and my best friend taught me to never use it either, not even when we were alone, for reasons having less to do with social justice than survival. Or maybe my best friend had just figured out how horrible the word was. He was gay, I think, though I left town before that surfaces. Likewise my mother’s family, and her racist mother, never used that word, either.

The word branded you as white trash. We weren’t necessarily enlightened. We were classist.

I can’t honestly remember being happy or sad about the move. It just was. But I loved watching the house be built that summer; pacing the foundation in the sea of mud. Walking into the basement from the backyard, as the property sloped downward and on that side, the basement had windows.

It would have been nice, if we had ever finished it. Or built a real deck onto the back of the house, where Joe and Carlio had hung a tiny balcony. But my parents salaries weren’t huge. Their retirement funds grew fantastically, but they weren’t allowed to ever touch them, which of course, is why my parents generation retired well, even the people in the middle class. So we never even poured a driveway over the gravel strip to the two car garage we started out with; which of course made plowing and shoveling the thing in the hideous Syracuse winters problematic.

My father hired a pickup with a plough, and it gouged up dirt and gravel.

My father hated any and all manual labor, so the large yard did nothing for my parents. My mother talked for seventeen years about putting in a garden, but only ever filled a little brick window box on the porch with petunias. They weren’t outdoor people. We never went camping. We never hiked. They never took us to parks. We never even got a swing set in that back yard, as we were ten and eleven and presumably needed to only wander the streets of the subdivision, or explore the vast tracks of undeveloped land surrounding us.

Which we did, and loved doing.

All this aside, I loved the suburbs, not knowing what I was missing, and for everything we missed, perhaps something was gained. Or did it it make into a person who enjoyed long lonely walks along mostly tamed wilderness? Who shrinks back from knowing the neighbors? We enjoyed the autonomy which would now be branded as neglect.

We never locked our doors. There was no mass transit. We rode bikes, but it was very hilly, glacially dumped Hobbiton mounds that were difficult to build on, and so, remained wild and lovely, poking up through the landscape sporting only the occasional pale blue water tower. Places for teens to drink and gaze out over a world of golf courses and ranch houses and drainage ditches, a vibrant but fading middle class, dying on the vine, like a cut flower, still colorful and bright as the manufacturing died and the big businesses all went bankrupt. The downtown that died, turning into a museum of a time gone by, shuttered by six o’clock every evening.

Except the University, Go Orange, which did just fine, becoming the cities biggest employer. My father had tenure. So we weren’t going anywhere, and we would never, ever want for anything, or even have the fear of wanting for anything.

Our only enemies lurked within. The restless madness of adolescence, the reason for armies and monasteries, the sequestering of violent young males. But there were no wars to send our testosterone poisoned, so instead, we went slowly mad in the weird toxic gasses given off by the cold war, the constant threat of annihilation, which troubled the thoughtful and which, like COVID today, was ignored by so many that the myth of the 80s now is one of patriotic exuberance, and not the punk counterculture gnawing at the tender trap of the fading post war dream.

Suburbia aged badly, like our Danish modern furniture, the nicks and scratches made it look like what it was; hastily constructed, a momentary fad, kinda cheap, and in the long run, not a good investment.

A shiny momentary dream of modernity to match the rockets racing to the moon, sputtering on the martini powered fumes of black and white JFK speeches, powered by Eisenhower’s prophesied monster, the military industrial complex.

I am old enough to love my childhood uncritically, minimizing the paralyzing fear of the dark, my ostracization and the suicidal misery of middle-school, the homophobic bullying, the hatred of high-school, the absurd early morning bus rides to wait forty five minutes for homeroom.

Instead I remember the gleaming hardwood floors of the new house, the light coming through the windows, sledding on the golf course with my friends, who all lived with a ten minute walk, snow forts and spelunking in drainage tunnels, junkyards, quarries, hallucinogenic adolescent ecstasies, vivid, violent, sexual awakening.

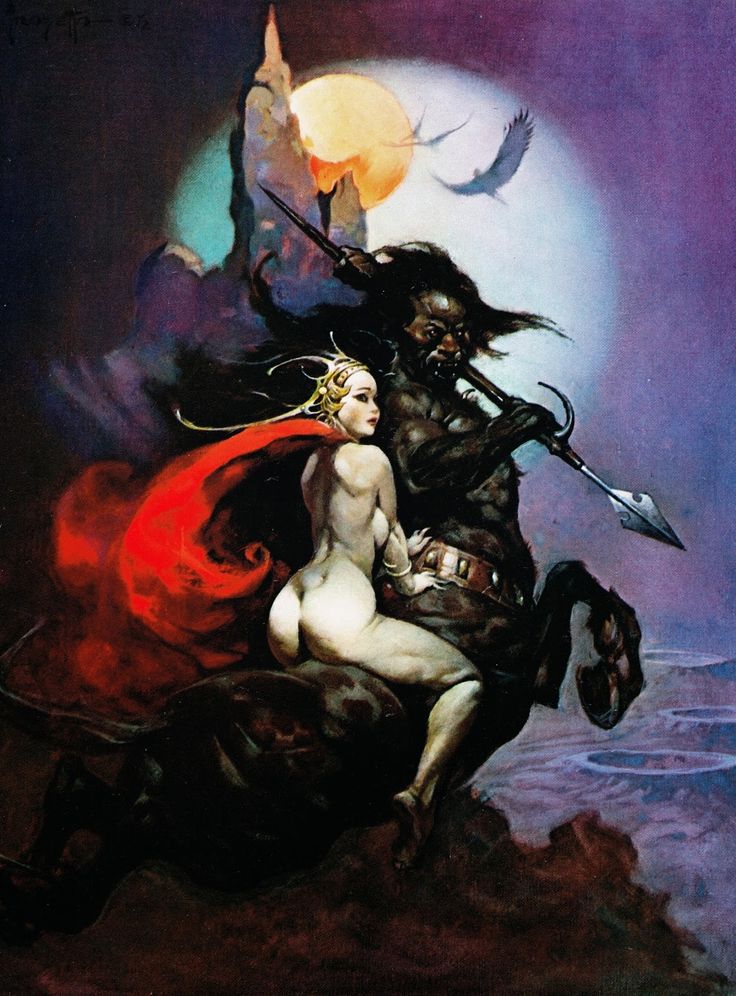

My first girlfriend, half nude in the steamed up car, her long, pale perfect body, the electricity of our touch. Orgasms like tactical nuclear explosions.

The skunky sweetness of burning weed, the icy cold cheap American beer, the future an endless road to anywhere and nowhere. I tested well, in school, very, very high, so high my half assed grade hardly mattered. We had enough money. I could and would go anywhere and do anything.

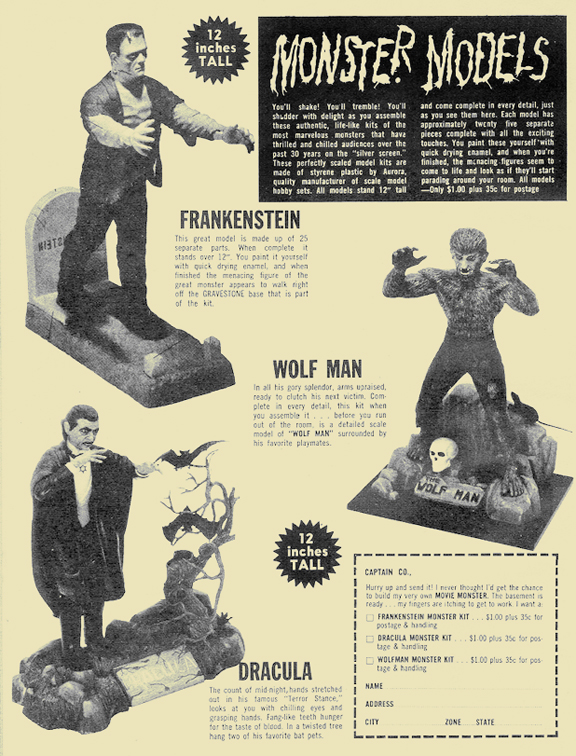

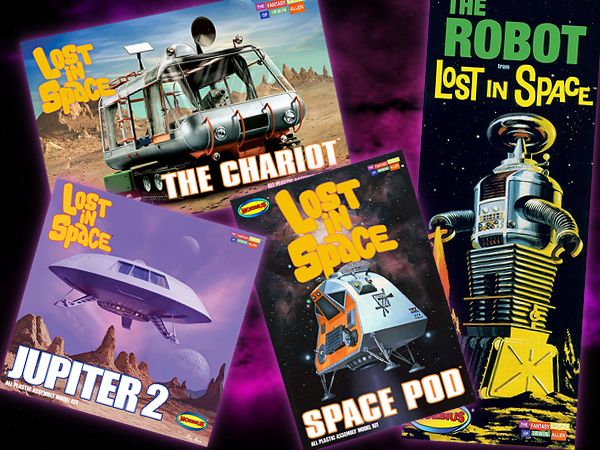

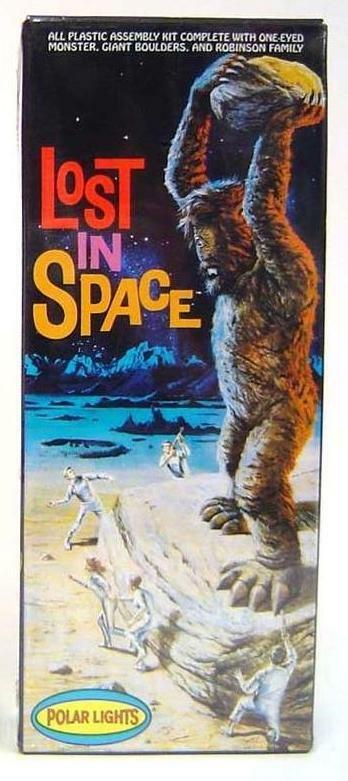

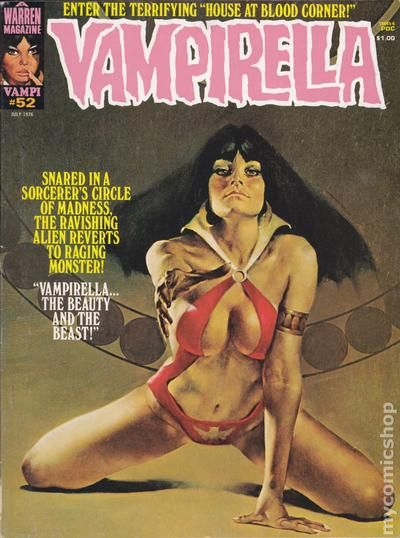

I close my eyes and I’m listening to the weekend drone of lawn mowers, smelling freshly cut grass through my open bedroom window, prowling stacks of discarded periodicals for Playboy magazines, tucking centerfolds in my back pockets, organizing my comic books, penciling dungeons onto graph paper, mastering my first campaign.

We went to war with orcs in middle earth. We initiated ourselves and each other with powerful drugs in cemeteries and on golfing greens. We kissed in steamed up cars. Made out with strangers in finished basements.

We waited for the futures to unfold, ready to spring away from the joyful, perfect, soul numbing safety and isolation of our subdivisions. To leave suburbia behind, and in my case, never go back.

Which we never did. But some part of me lingers, never leaving, roaming that undeveloped land that is now packed with newer, even more souless McMansions. The past a different country, that boy a stranger I don’t really remember being.

Back when the suburbs seemed like a good idea.

Back when the suburbs sang.